If you come from a SQL Server background (like in my case), you already have strong instincts about indexing. You know why B-trees dominate, why sorted structures matter, and why equality predicates are usually fast enough without special tricks. When you first encounter Hash Indexes in PostgreSQL, the obvious question is not how they work, but why they exist at all.

After all, SQL Server never needed a separate hash index type for its traditional disk-based engine. And if you’ve worked with In-Memory OLTP, you may already associate hash indexes with something very different and far more specialized.

This blog posting is about building the right mental model – one that aligns PostgreSQL hash indexes with what you already know, without confusing them with SQL Server’s in-memory world.

The Shared Baseline: Why B-Trees Dominate Everywhere

Both SQL Server and PostgreSQL rely on B-trees as their default indexing structure for a simple reason: they are extraordinarily flexible. Equality lookups, range scans, ordered output, prefix searches, merge joins – all of these flow naturally from sorted keys.

This is why, in PostgreSQL just as in SQL Server, the B-tree is the “do-everything” index. It is rarely the fastest possible structure for any single operation, but it is consistently good across almost all query shapes. That universality sets the context for understanding hash indexes correctly.

Hash indexes are not introduced because B-trees are insufficient. They exist because sometimes the additional capabilities of a B-tree are simply unnecessary overhead.

What a PostgreSQL Hash Index Really Represents

A PostgreSQL hash index deliberately abandons ordering. Instead of maintaining keys in sorted order, it applies a hash function to the indexed value and uses the resulting hash to navigate directly to a bucket containing matching entries.

This is a crucial conceptual shift for SQL Server professionals. A hash index in PostgreSQL is not a general indexing strategy. It is a narrow contract between the schema designer and the query planner.

If the contract is honored – strict equality predicates and nothing else – the index can do less work. If the contract is broken, the index becomes useless.

Equality Without Ordering: Why That Can Still Matter

At first glance, this feels like an academic distinction. B-trees handle equality extremely well, both in SQL Server and PostgreSQL. In most systems, equality lookups are already cheap enough that shaving off a little extra overhead seems irrelevant.

The difference emerges only in highly repetitive, narrowly scoped workloads. A hash index avoids the cost of maintaining a order during inserts and updates. It does not need to care about neighboring keys or tree balance in the same way. Under the right conditions, that simplicity can translate into slightly lower maintenance overhead and very direct lookup paths.

Creating and Using a Hash Index in PostgreSQL

To make this tangible, consider a simple table that behaves like a key/value store. Imagine a session table where every lookup is performed by an exact session token.

-- Create a simple table

CREATE TABLE Sessions

(

SessionID TEXT PRIMARY KEY,

UserID TEXT NOT NULL,

CreatedTimestamp TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- Insert 10mio records

INSERT INTO Sessions (SessionID, UserID)

SELECT

'Session_' || s,

'User' || s || '@sqlpassion.at'

FROM generate_series(1, 10000000) s;If the workload consists almost entirely of queries like this:

SELECT UserID

FROM Sessions

WHERE SessionID = '424242';then ordering is irrelevant. There will never be a range predicate, never an ORDER BY SessionID, and never a prefix search. In this case, you can explicitly create a hash index:

-- Create a Hash Index

CREATE INDEX idx_SessionID ON Sessions

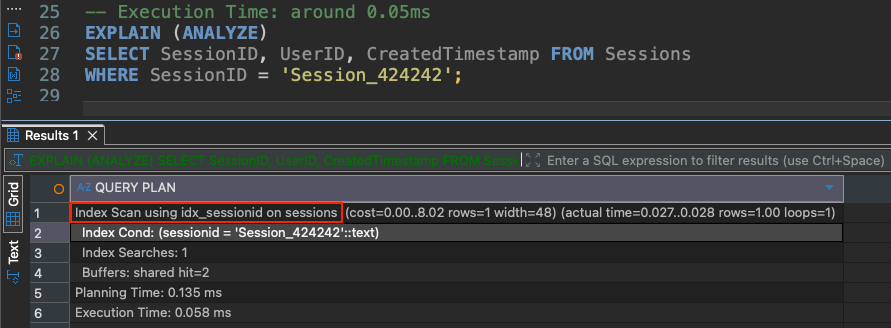

USING hash (SessionID);PostgreSQL can now use this index for equality lookups. An EXPLAIN plan will show an index scan using the hash index when the query planner determines it is the cheapest path.

What is important here is not the syntax – it is the intention. By choosing a hash index, you are telling PostgreSQL that this column exists purely for exact matching. If that assumption changes later, the index choice must be revisited.

Why the Query Planner Is Conservative About Hash Indexes

PostgreSQL’s query planner does not aggressively favour hash indexes. Even when a hash index exists, the query planner may still choose a B-tree if it believes the B-tree offers comparable cost with more flexibility. This mirrors SQL Server’s behavior. The query optimizer tends to prefer structures that keep options open. A hash index is only attractive when its limitations are irrelevant to the query.

As a result, many PostgreSQL systems contain hash indexes that are technically valid but practically unused. This is not a failure of the database engine – it is a sign that the workload does not truly justify such specialization.

Where Hash Indexes Can Genuinely Fit

Hash indexes make sense in PostgreSQL when the data access pattern resembles a lookup table more than a relational structure. Session stores, token tables, exact-match joins on surrogate keys, or fact tables accessed exclusively via immutable identifiers are common examples.

In each of these cases, the column in question behaves more like a dictionary key than a sortable attribute. When that mental model holds, hashing aligns well with reality. The moment you need ordering, grouping, or range filtering, the model breaks down – and so does the usefulness of the hash index.

Hash Indexes vs. SQL Server In-Memory OLTP

This brings us to the most common – and most dangerous – misunderstanding.

SQL Server In-Memory OLTP hash indexes belong to a completely different universe. They live inside a specialized engine, require explicit bucket sizing, and are designed for latch-free, memory-resident execution. Choosing them is a fundamental architectural decision.

PostgreSQL hash indexes are nothing like that. SQL Server In-Memory hash indexes are like a full triathlon bike setup: aggressive geometry, deep carbon wheels, and a carefully chosen cassette that only makes sense if the course profile is known in advance. If the gearing is wrong or the terrain changes, performance suffers immediately.

PostgreSQL hash indexes, by contrast, are more like swapping the cassette on a road bike for a very flat race. You are not changing the bike, the frame, or the discipline. You are simply choosing a narrower gear range because you know the course is straight, predictable, and repetitive.

That distinction matters. One is an engine choice. The other is a tactical adjustment.

Summary

For SQL Server professionals transitioning to PostgreSQL, the safest approach is to treat hash indexes as deliberate exceptions. They are not performance hacks and they are not equivalents of In-Memory OLTP constructs. They are simple tools for simple promises: this column will only ever be compared for equality.

When that promise holds, a hash index can be elegant. When it does not, the B-tree you already trust remains the right answer – both in databases and in life.

Thanks for your time,

-Klaus