When SQL Server professionals start working seriously with PostgreSQL, most of the learning curve feels comfortable. Tables behave as expected, transactions are familiar, and B-tree indexes look reassuringly similar to what you have used for years in SQL Server. Then you encounter BRIN indexes.

At first glance, they seem almost reckless: no row pointers, no precise navigation, and an explicit acceptance of false positives. And yet, on very large tables, BRIN indexes often deliver performance gains that would require clustered indexes, partitioning, or even columnstore indexes in SQL Server. To understand why, we need to look not only at what BRIN does, but how it works internally.

👉 If you want to learn more about SQL Server 2025 and PostgreSQL, I highly recommend to have a look on my upcoming online trainings about it.

From Precision to Probability

SQL Server indexing is built around precision. A nonclustered index maps keys to row locators. A clustered index defines the physical layout of the table itself. Performance tuning is about choosing the correct key order and keeping fragmentation under control.

PostgreSQL can do all of that too. But it also embraces a different idea: sometimes you don’t need to know where a row is – it is enough to know where rows cannot be. BRIN, short for Block Range Index, is the embodiment of that idea.

PostgreSQL stores tables as collections of 8 KB heap pages. A BRIN index groups these pages into block ranges, typically 128 heap pages per range (about 1 MB of data). For each range, PostgreSQL stores only summary information, most commonly the minimum and maximum value of the indexed column. Crucially, a BRIN index does not store page IDs or row pointers.

This is a fundamental difference compared to B-tree indexes and SQL Server nonclustered indexes. There is no list of heap pages associated with a range. Instead, the relationship between a BRIN index entry and the table is implicit. The position of a BRIN index tuple is the address of the block range.

- Range 0 corresponds to heap pages 0 – 127

- Range 1 corresponds to heap pages 128 – 255

- Range N corresponds to heap pages N × pages_per_range through (N+1) × pages_per_range – 1

No pointers are stored because none are needed. PostgreSQL derives the heap pages mathematically. This design choice is one of the main reasons BRIN indexes are so small and so fast.

What Happens During Query Execution

When a query arrives with a predicate such as a timestamp range, PostgreSQL scans the BRIN index sequentially. For each block range, it compares the query predicate with the stored minimum and maximum values. If the predicate lies completely outside the range, PostgreSQL can skip that entire block range without reading a single heap page. If the predicate might match, the range is marked as a candidate and only those heap pages are scanned.

False positives are expected and acceptable. The cost of checking a few extra pages is negligible compared to scanning the entire table. Because the mapping between index entry and heap pages is implicit, the overhead is minimal: no pointer chasing, no tree traversal, and excellent cache locality.

A Concrete Example: Large Time-Series Data

Consider a classic logging or event table: append-only, ordered by time, and very large. This is exactly the kind of workload BRIN was designed for.

-- Create a simple table

CREATE TABLE Events

(

ID BIGINT GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY,

Ts TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL,

DeviceID INT NOT NULL,

Payload TEXT NOT NULL

);

-- Insert some test data

INSERT INTO Events (Ts, DeviceID, Payload)

SELECT

TIMESTAMPTZ '2025-01-01 00:00:00+00' + MAKE_INTERVAL(secs => g),

(g % 1000) + 1,

MD5(g::TEXT)

FROM GENERATE_SERIES(1, 20000000) AS g;

-- Update Statistics

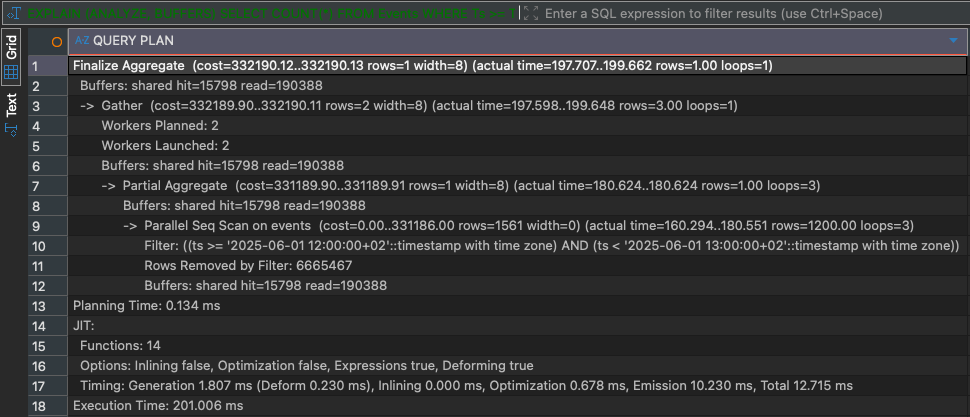

ANALYZE Events;With 20 million rows inserted in strictly increasing timestamp order, the physical layout of the table aligns perfectly with time-based queries. A query that filters a single hour still has to examine a large portion of the table without an index. The following query takes around 200ms on my system:

-- Parallel Sequential Scan

-- Execution Time: 200ms

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS)

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Events

WHERE

Ts >= TIMESTAMPTZ '2025-06-01 10:00:00+00'

AND Ts < TIMESTAMPTZ '2025-06-01 11:00:00+00';

Now, let’s add a BRIN index:

-- Create a BRIN Index

CREATE INDEX idx_Events_Ts_Brin

ON Events

USING BRIN (Ts)

WITH (pages_per_range = 128);

-- Update Statistics

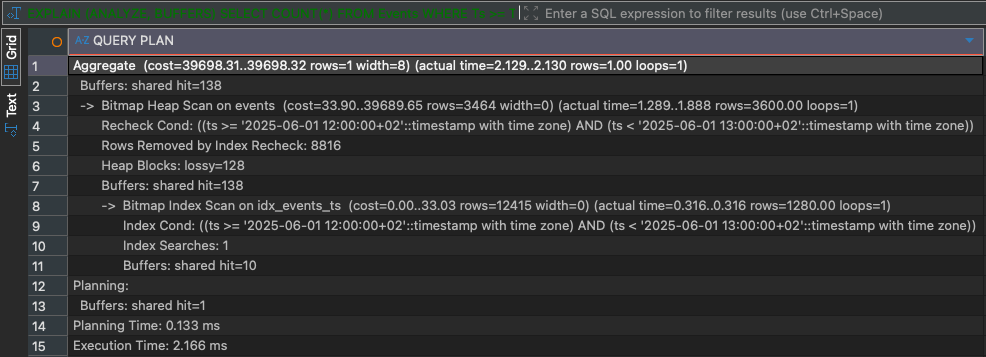

ANALYZE Events;Running the same query again shows a different execution plan. PostgreSQL uses the BRIN index to identify a small number of relevant block ranges and reads only those heap pages. The buffer statistics make the benefit obvious: far fewer pages are touched. The query runs now for about 2ms:

-- Bitmap Index/Heap Scan

-- Execution Time: 2ms

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS)

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Events

WHERE

Ts >= TIMESTAMPTZ '2025-06-01 10:00:00+00'

AND Ts < TIMESTAMPTZ '2025-06-01 11:00:00+00';

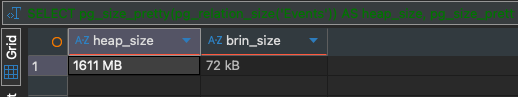

Even more interesting is the size comparison:

-- The BRIN index is very small

SELECT

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('Events')) AS heap_size,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('idx_Events_Ts')) AS brin_size;The BRIN index is very small, and only has a size of around 72KB – in comparison to 1611MB of the whole heap table. On a table with tens of millions of rows, the BRIN index is often measured in kilobytes or a few megabytes:

Why This Feels Unfamiliar to SQL Server Experts

From a SQL Server perspective, this approach feels unusual. A clustered index on a timestamp column would give similar range-scan performance, but at the cost of a large index structure and ongoing maintenance. Partitioning could reduce scan scope, but introduces administrative complexity. Columnstore indexes use segment-level metadata with MIN and MAX values, which is conceptually close to BRIN, but they come with a very different execution engine and workload profile.

BRIN can be thought of as automatic, ultra-lightweight, intra-table partition pruning. It achieves much of the benefit of these SQL Server techniques with a fraction of the overhead.

The Trade-Offs: When BRIN Fails

BRIN’s efficiency depends on data correlation. If values are randomly distributed, the minimum and maximum values of block ranges overlap heavily. In that case, most ranges become candidates and PostgreSQL ends up scanning large portions of the table anyway.

BRIN is also unsuitable for point lookups. Queries that search for a specific ID or require high precision still need B-tree indexes. BRIN is designed to reduce the search space, not to pinpoint rows.

Another subtle drawback is cost estimation. Because BRIN is coarse by nature, the planner may misestimate selectivity, especially on smaller tables. In those cases, PostgreSQL may correctly decide that a sequential scan is cheaper.

The key insight for SQL Server professionals is that BRIN is not a replacement for B-tree indexes. It is a complementary tool. In PostgreSQL, it is common – and powerful – to combine precise B-tree indexes for OLTP access with BRIN indexes for large-scale analytical scans on the same table. Each index serves a different purpose, and together they often outperform more complex designs.

Summary

BRIN indexes highlight a deeper philosophical difference between PostgreSQL and SQL Server. SQL Server emphasizes precision and carefully engineered index structures. PostgreSQL, with BRIN, embraces the idea that an index can be imperfect as long as it is cheap and effective at scale.

Once you internalize that, BRIN stops feeling strange. It starts to feel like a pragmatic optimization that trades precision for simplicity – and wins.

For SQL Server professionals moving into PostgreSQL, understanding BRIN is more than learning a new index type. It is learning a new way of thinking about performance.

👉 If you want to learn more about SQL Server 2025 and PostgreSQL, I highly recommend to have a look on my upcoming online trainings about it.

Thanks for your time,

-Klaus