If you come from SQL Server (like in my case), PostgreSQL indexing can feel familiar at first – B-tree indexes exist, composite indexes exist, covering indexes exist. And then you run into queries like this:

WHERE payload @> '{"type":"payment","status":"failed"}'or this:

WHERE tsv @@ plainto_tsquery('postgresql')At that point, most SQL Server developers ask two questions:

- What are these operators?

- Why does PostgreSQL need a completely different index type for this?

This blog posting answers both questions – and shows why GIN indexes exist, what problems they solve, and how they compare to modern SQL Server (including SQL Server 2025 with native JSON indexes).

👉 If you want to learn more about SQL Server 2025 and PostgreSQL, I highly recommend to have a look on my upcoming online trainings about it.

First Things First: PostgreSQL Indexes Are Operator-Driven

PostgreSQL uses a fundamentally different indexing philosophy than SQL Server. In SQL Server, indexes are:

- Column-based

- Value-based

- Optimized for equality, range, and order

In PostgreSQL, indexes are:

- operator-based

- designed around how data is queried, not just how it is stored

This is why PostgreSQL has operators that look unfamiliar – but are actually very explicit.

Understanding the Two Key Operators

Before talking about GIN, you must understand what these operators mean.

The @> operator means “contains”:

payload @> '{"type":"payment"}'This means: “Does the JSON document in payload contain at least this key/value pair?“

It does not require:

- Identical JSON

- Identical ordering

- Identical structure beyond the keys provided

This is very different from SQL Server’s traditional JSON functions, which historically required explicit extraction. Before SQL Server 2025, you typically wrote:

JSON_VALUE(payload, '$.type') = 'payment'And indexed that via:

- Persisted computed columns

- Or filtered indexes

SQL Server 2025 improves this by introducing:

- Native JSON data type

- JSON indexes

However, those indexes still operate on paths and values, not on arbitrary JSON containment semantics. PostgreSQL’s @> operator answers a higher-level question: “Does this document logically include this structure?“

On the other hand, the @@ operator is used for full-text search:

tsv @@ plainto_tsquery('postgresql')This means: “Does this document’s token vector match this text query?“

Think of it as:

- Not LIKE

- Not string comparison

- But linguistic matching

SQL Server developers should compare this to Full-Text Search predicates, not to LIKE ‘%text%’.

The Need for GIN Indexes

B-tree indexes work when:

- One row = one indexed value

- Comparisons are equality or range based

- Ordering matters

A GIN (Generalized Inverted Index) is an inverted index. Instead of storing:

Row -> Value

It stores:

Value -> Many Rows

Each searchable element inside a column becomes its own index key. This is why GIN is ideal for:

- JSONB

- Arrays

- Tags

- Full-Text tokens

A Concrete Example

Let’s create a simple table that stores payment processing information:

-- Create a simple table

CREATE TABLE Events

(

ID BIGINT GENERATED ALWAYS AS IDENTITY,

OccurredAt TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL,

Payload JSONB NOT NULL

);It will store in the column Payload the following JSON document:

{

"type": "payment",

"status": "failed",

"user_id": 4711,

"tags": ["stripe", "europe"]

}Let’s insert some test data:

-- Insert 1mio rows

INSERT INTO Events (OccurredAt, Payload)

SELECT

now() - (random() * interval '30 days'),

jsonb_build_object(

'type',

CASE

WHEN r < 0.80 THEN 'payment'

WHEN r < 0.95 THEN 'login'

ELSE 'signup'

END,

'status',

CASE

WHEN r < 0.80 THEN

CASE WHEN random() < 0.002 THEN 'failed' ELSE 'success' END

ELSE

CASE WHEN random() < 0.01 THEN 'failed' ELSE 'success' END

END,

'user_id', (random() * 5000000)::int,

'region', CASE WHEN random() < 0.6 THEN 'eu' ELSE 'us' END,

'provider',CASE WHEN random() < 0.5 THEN 'stripe' ELSE 'paypal' END,

'tags',

CASE

WHEN random() < 0.20 THEN jsonb_build_array('retry','europe')

WHEN random() < 0.40 THEN jsonb_build_array('stripe','europe')

WHEN random() < 0.60 THEN jsonb_build_array('paypal','us')

ELSE jsonb_build_array('mobile','web')

END

)

FROM (

SELECT random() AS r

FROM generate_series(1, 1000000)

) s;

-- Update Statistics

ANALYZE events;And now we have the following query that we want to optimize:

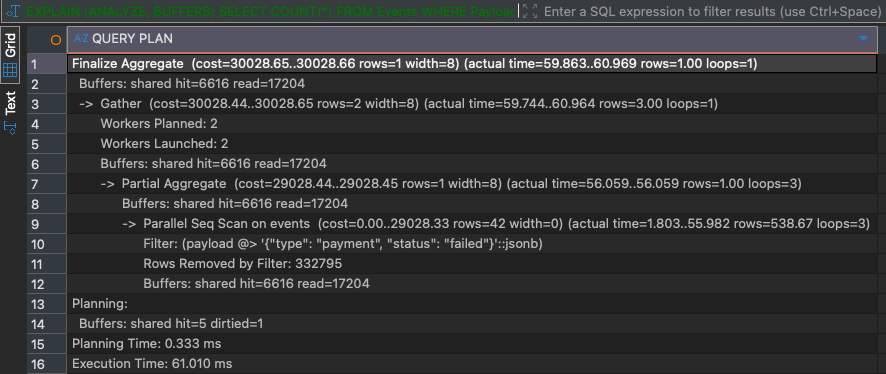

-- Execution Time: around 60ms

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS)

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM Events

WHERE Payload @> '{"type":"payment","status":"failed"}'::JSONB;Without any index in place, this query runs for about 60ms on my system:

Let’s create a GIN index:

-- Create a GIN index

CREATE INDEX idx_EventsPayload_GIN

ON Events

USING GIN(Payload);

-- Update Statistics

ANALYZE events;That single statement indexes:

- Every JSON key

- Every JSON value

- Every array element

This is something SQL Server JSON indexes – even in SQL Server 2025 – do not model the same way, because they remain path-centric rather than containment-centric.

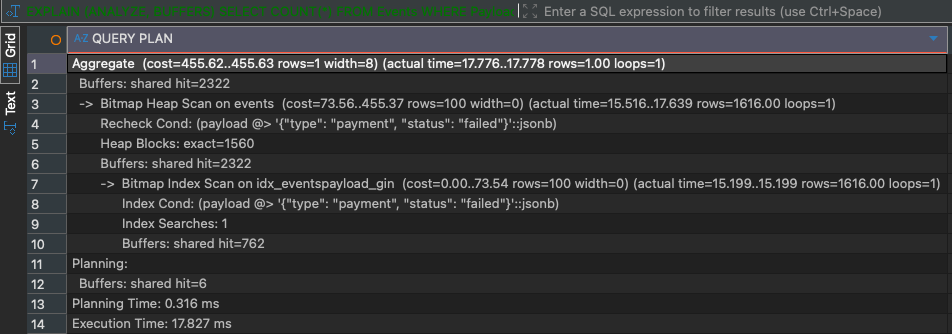

When we run now the query again, the query planner uses the GIN index, and the query finishes in around 18ms:

But GIN indexes also have some negative side-effects:

- Larger than B-Trees

- Slow down Inserts and Updates

- Do not support ordering

That last point is very critical – and leads directly to RUM.

What is RUM?

RUM is an extension, not a built-in index type. It extends GIN by storing:

- Token positions

- Ranking metadata

- Optional ordering hints

CREATE EXTENSION rum;

CREATE INDEX idx_Documents_RUM

ON Documents

USING RUM (tsv rum_tsvector_ops);Now PostgreSQL can:

- Filter

- Rank

- and partially order results index the index

Summary

Yes, SQL Server 2025 significantly improves JSON support. But PostgreSQL’s GIN model was never about JSON alone – it is about indexing meaning, not just values. GIN exists because modern data is:

- Multi-valued

- Semi-structured

- Queried semantically

RUM exists because once filtering is cheap, relevance matters. If you approach PostgreSQL with this mindset, GIN indexes stop being “weird” – and start feeling inevitable.

👉 If you want to learn more about SQL Server 2025 and PostgreSQL, I highly recommend to have a look on my upcoming online trainings about it.

Thanks for your time,

-Klaus